The most original film I saw at this year’s Japan Cuts 2024 Festival was Gen Nagao’s “Motion Picture: Choke.” It seems to have come out of nowhere. I can’t find anything about it on IMDB. There are no beginning titles or end credits. It’s a dystopian story filmed in black and white about the few survivors of an apocalyptic event that destroyed the world. We’ve seen many stories like this but the unique aspect of this one is that the humans have lost their verbal language abilities. No explanation is given and any speculation about how this happened would be futile.

We are first introduced to a young woman (a mesmerizing performance by Misa Wada) living in a partially destroyed building. Though alone, she seems to enjoy her daily routines: fetching water from a nearby stream, bathing there, catching small birds to eat and collecting other foods. When it rains she puts buckets out to catch it and performs some miscellaneous percussion accompaniment to the rain drops that gives her immense satisfaction. Her dreams, though, often include nightmares of a dark shape moving above her while she sleeps, sometimes revealing a frightening pair of cartoonish eyes. Is this a memory of someone from her past?

She meets occasionally with an elderly man to trade wares: dried meat (fish?) and trinkets, including a round magnifying glass. He shows her how to use it to start a fire. Her happy-go-lucky life is disrupted when a trio of bandits attack her. The eldest (Takashi Nishina) rapes her. They steal her fire-starting glass and leave.

After a period of trauma she is visited by a young man (Daiki Hiba) whom she captures but after realizing how sweet and harmless he is, she gradually lets him be her helper and they eventually become lovers. The film is at its best in the scenes in which they learn to communicate and bond through gestures and looks. They build an aqueduct from the stream to the building using a series of connected bamboo poles. Their lives become easier, leaving them more leisure time.

When the elderly bandit returns, the trust between the young man and woman is tried with disastrous results. It’s unclear what the unpredictable, imaginatively edited ending suggests. The end of a possible matriarchy (which historians and archaeologists now think may never have existed unambiguously)? Or an example of the changes in human consciousness that represented leaps or falls that must have been terrifying to those early beings.

The opening credits of Truffaut’s 1966 adaptation of “Fahrenheit 451” were delivered in spoken words over photos of TV antennas to suggest a new world without written language in that dystopian fable. Here the lack of any text on screen is used with a similar strategy. A brilliant soundtrack that seems to have come from the 1950’s begins and interrupts the film accompanied by black screen, as if training the viewer’s senses before the first images appear. Like the opening sequence of Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” there is no getting around the fact that we are understanding each film in a visual language that did not exist until the 20th century. But Nagao’s masterful film still succeeds in challenging our minds in ways few films do–it is a haunting, visionary work.

Director Yoshimasa Ishibashi’s “Six Singing Women” is an allegorical ecofiction film. Kayajima (Yutaka Takenouchi) is a Tokyo-based photographer who has just inherited his childhood home from an estranged father. He wants nothing to do with the home of a dad he never knew, a place he lived in for only a few years as a child. He travels there, hoping to stay only the few hours necessary to sell it to Uwajima (Takayuki Yamada), a real-estate developer whose corporation plans to tear it and the surrounding forest down, which will create an ecological disaster for the nearby residents.

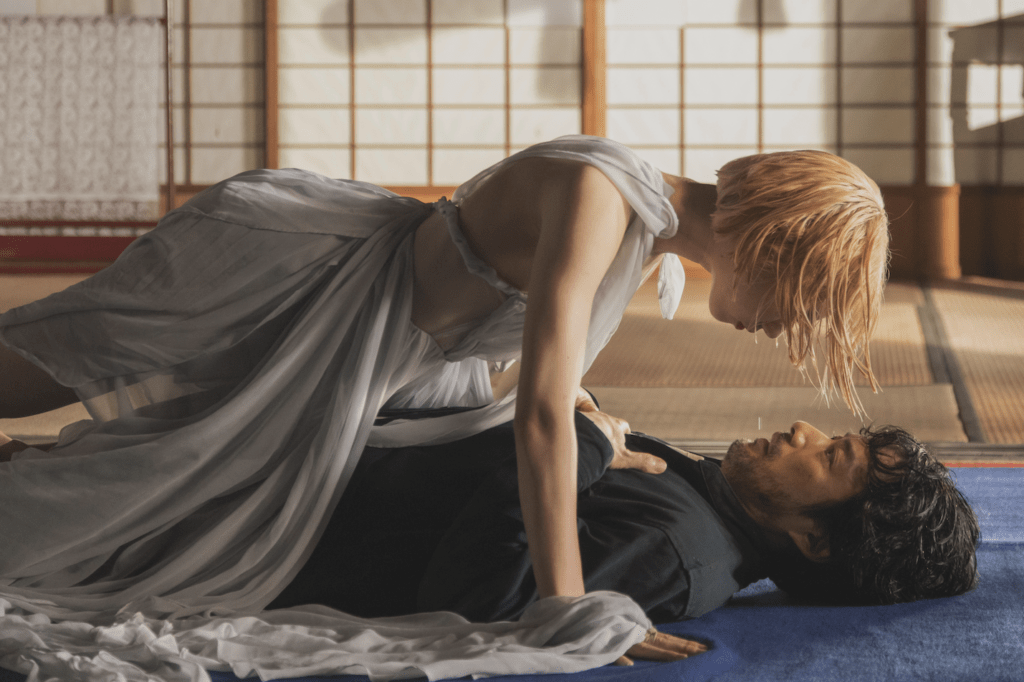

His short visit is prolonged by the appearance of six female apparitions, each of whom vex the mission of the greedy developer and stimulate the photographer’s memories of childhood and rekindle his love of nature and his relationship with his parents as he contemplates becoming a father himself soon. Though never identified by name in the film, the trailer brands them with individual characteristics: the woman who stabs, the woman who bears fangs, the woman who envelops, the woman who stars, the woman who is wet and the woman who scatters. They are each terrifying and beautiful and mute. The film works well both as an erotic thriller and environmental horror story, with gorgeous visuals and fine performances by the leads and the six female ghosts. (Who don’t actually “sing” and who may have been more effective if they had actually been given dialogue.)

“The Box Man,” directed by Gakuryu Ishii, is based on a 1973 novel by Kōbō Abe, whose 1962 novel “The Woman in the Dunes” was made into the classic film by Hiroshi Teshigahara.

A nameless man (Masatoshi Nagase) lives in a large cardboard box with a small opening he looks out of. (The 16:9 aperture ratio of this window suggests a cinematic viewpoint.) The inside of his box is decorated with photographs he takes with an analog camera. (He develops the negatives in the box!)

The story is narrated with philosophical takes on what it means to be a “box man” and why anyone who becomes obsessed with the box man will become one too. The soundtrack features outbursts of strident Japanese metal pop. (Ishii was once part of a noise pop band.) The narrative is not easy to follow: the identity of the box man may be that of a rich man or a “fake doctor” who both attempt to control the box man. An alluring “fake nurse” is also part of the complex scheme.

Though written in the 1970’s, this film version seems to be commenting on the disturbing combination of insularity and influencing mechanics contemporary social media has poisoned us with. While not completely successful as a cautionary fable, its wild assortment of visual and aural treats make this uniquely entertaining film a must-see for fans of anarchic cinema.