We were told in Film History 101 that spectators who first saw the Lumière brothers’ 1896 film of a train rushing forward (“Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat”) scared the audience, who thought it was going to leap from the screen and hit them. Turns out this didn’t really happen. We were also told that it took a long time for audiences to understand the film grammar rapidly formulated in the first two decades of film. Spectators didn’t understand what would later be called “continuity editing.” A new documentary challenges these views, using testimony by a notable film scholar, a legendary film editor and the experiments of several psychologists to describe how people learned very quickly to understand these radical shifts in what became the most important medium of the twentieth century. “The Cinema Within: A Documentary about the Psychology of Film Editing” is available for streaming on Amazon and Apple TV beginning May 20. The DVD is also for sale starting that day and you can watch for free if you have a Kanopy account from your local public library. Go here for more information about the film.

David Bordwell died last year; I was lucky to have seen him do a lecture at UNC-Chapel Hill once. When the first edition of his textbook “Film Art: An Introduction” came out in 1979 it was a sensation for film students and has gone through twelve editions. Though formalist criticism was becoming frowned upon in art history and other disciplines, the previous decades of books on film had been mostly sociological. It was refreshing to see a textbook that talked about the formal properties of films and included actual frame captures rather than studio film stills. In a later book, 1985’s “Narration and the Fiction Film,” Bordwell became a pioneer of cognitive film theory, a study of the psychological basis of film form and storytelling.

A scene from Ozu’s 1953 classic, “Tokyo Story,” (a director Bordwell devoted a whole book to) is shown as he points out that the actors look directly at each other and never blink. This “ratchets” up our attention. Later he discusses the way cross-cutting (invented in early silent films) engages us.

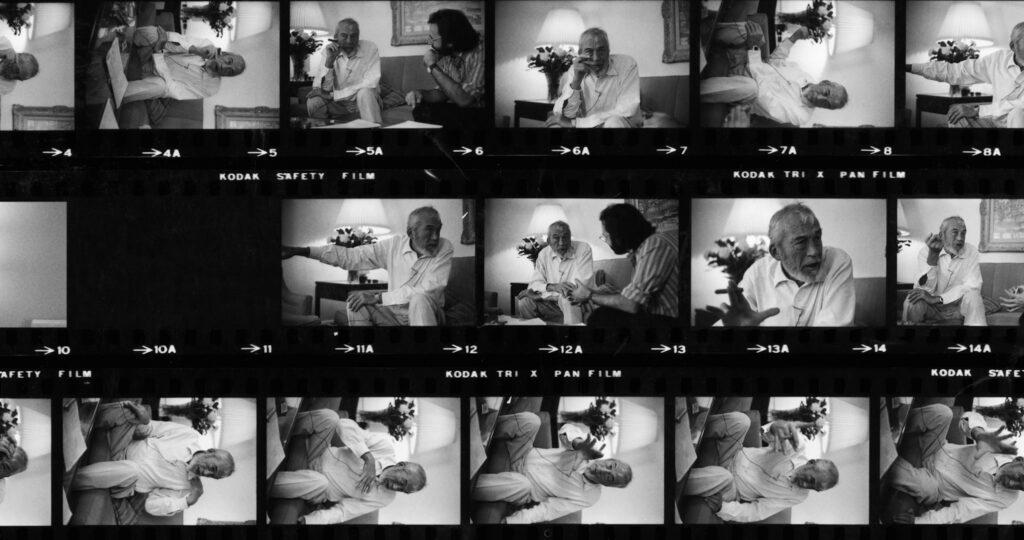

But Walter Murch has a different theory of blinking. Working early into the morning while editing Coppola’s 1974 film “The Conversation,” Murch began to notice the eye blinks of actor Gene Hackman in a key scene. Later, in a chance reading of an interview with director John Huston, he noted his demonstration (one that was photographed; see the contact print below) of why you shouldn’t use a pan instead of a cut when going from (in his example) one lamp in a room to another. You blink your eye as you pan from one to the other, he told the interviewer. (When I try this out myself I find I don’t blink when panning but as a visual artist my eyes are trained very differently than most viewers.) In 1992 Murch published his classic book about film editing, “In the Blink of An Eye,” and the film uses actors to reconstruct the lecture Murch gave that became the basis of that work.

Other scientists are presented who actually have studied the way we blink but the researcher whose work is featured predominantly here is Sermin Ildirar, a researcher at the University of London who visited a group of people living in a remote location in Turkey who had never seen movies before. She published a well-received academic paper in 2009 in which she documented her work: she showed a set of film clips shot in their village demonstrating “perceptual discontinuities typical for film.” She discovered that “natural perception” alone couldn’t help the study participants to understand the cuts. But a “familiar line of action” helped them to understand some clips.

Directed and edited by Chad Freidrichs (whose previous work includes the excellent music doc “Jandek on Corwood” and the much-lauded “The Pruitt-Igoe Myth”), this is an entertaining, thought-provoking and well-edited film. (One notable lapse, though, is a consideration of the way pre-cinema mediums prepared viewers for understanding film editing–cartoon strips in newspapers, for example.)